First, I want to thank The Tundra PA for keeping us up to date on this year’s race. Here is her most recent report:

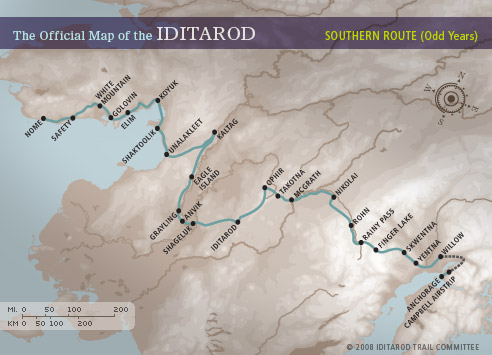

Happy Thursday everyone! I keep posting the race map because it seems to me to be the easiest way to understand where things are in the race; but then I’m a “map-oriented” kind of person. If it’s not helpful, somebody tell me and I’ll stop.

So the good news is that Aliy is still in the lead, and was the first musher into the ghost town of Iditarod which means she wins the Halfway Award–$3,000 worth of gold nuggets! Sweet! But as she said in the short video of her arrival, she’d rather win the All-The-Way award. The bad news is that her lead position is about to be overtaken.

The two dominant teams in the race so far are Nicolas Petit, the 38-year-old Frenchman, and Joar (pronounced “Yar”) Ulsom, the 32-year-old Norweigan. All the sage pundits are saying that they are the teams to beat, and Aliy is the wild card, the one most likely to have a chance to do so. She started her 24 hour rest about 8 hours ago, so cannot leave Iditarod check point until around 2 am on Friday. Nic and Joar took their 24s back at Ophir and Takotna, have completed their time and are moving quickly; they are now about 4 hours behind Aliy. They will be many miles down the trail before she can leave.

But weather is always a factor in this race. Winter storms are battering the coast of the Bering Sea where they are all headed and that can change everything.

The battle between Nic and Joar is something of a grudge match from last year’s race. Joar won and Nic was second. But when they were some 200 miles from the finish last year, Nic was substantially in the lead and seemed uncatchable. But then he made a devastating mistake and took a wrong turn and lost the trail. He wasted over two hours before discovering the mistake and getting back on track. In the meantime, Joar passed him and the rest was history. Nic is totally fired up this year to make up for that. The question will be whether Aliy can bust those plans. Time will tell. Meanwhile, it’s kind of thumb-twiddling time until everyone finishes their 24.

Go Aliy! Go dogs!

I thought I would recap a bit of the history about the Iditarod race, most of it from previous years’ posts.

I thought I would recap a bit of the history about the Iditarod race, most of it from previous years’ posts.

Cody Strathe’s team leaves the restart of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race in Willow, Alaska. REUTERS/Nathaniel Wilder

The Iditarod is an exciting dog-sled race from Anchorage to Nome – a total distance of 975 miles. It is exciting even in our modern, perhaps jaded, view, but the story behind this race is historic.

Alaska in winter can be a treacherous place. The modern race is as safe as it can be made, with regular checkpoints, where supplies have been pre-placed, and mushers and their dogs can rest along the way.

The original “Iditarod” was another matter, indeed.

In 1925, long before there was an Alaskan Highway, Nome was isolated for months out of the year. The only way to get to Nome was by dog sled. No ships or planes or cars or trucks could get to Nome in winter.

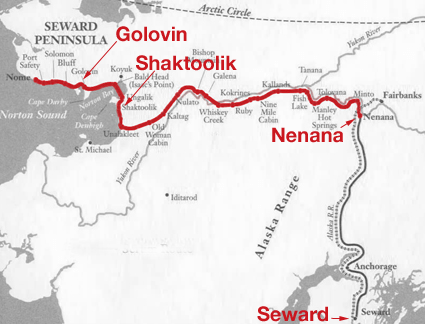

In the late 1890′s and early 1900′s, settlers had come to Alaska following a gold strike. They traveled by boat to the coastal towns of Seward and Knik and from there, by land into the gold fields. The trail they used is today known as The Iditarod Trail, first surveyed by the Alaska Road Commission in 1908 and now one of the National Historic Trails as so designated by the Congress of the United States. In the winter, their only means of travel was by dog team.

The Iditarod Trail soon became the major “thoroughfare” through Alaska. Mail was carried across this trail, people used the trail to get from place to place and supplies were transported via the Iditarod Trail. Priests, ministers and judges traveled between villages via dog team.

The dogs and sleds were there long before the settlers came from the lower states, of course. The native population had used them for centuries. According to “Dog Sledding’s History and Rise (dogsled.com),

It is believed that dog sledding has started in the arctic region. These regions are covered in ice and no transportation was possible. Horses could not last in the harsh arctic region. But the dogs were better solution to this problem. Dogs’ endurance was much greater than the endurance of a horse and they could survive treacherous terrain much better. A team of six dogs could handle 500 to 700 pounds on one sled. That’s why dog sledding became popular in arctic region. Archaeological evidence shows dog sledding in Canada, North America, and Siberia originated 4000 years ago. The Inuit used dog power for traveling from one place to another. They were also used for hunting and monitoring trap lines in the Canadian arctic wilderness. Inuit invented the dog sled which was pulled by the dogs. This sled was made of a mid range floating basket and a piece of wood. It was known as “komatik”.

Back to the story of the original, 1925, Great Race to Nome:

In December 1924, the first diphtheria-like illness was reported in the native village of Holy Cross, just a few miles away from Nome. The two-year old boy died the next morning. His parents, who were native Inuits, would not allow his body to be autopsied. As a result, three more children in the same area died with similar symptoms before the local doctor, Dr. Curtis Welch, could diagnose their illness as diphtheria.

On January 20, 1925, a three-year old child was properly diagnosed with diphtheria. Dr. Welch had six thousand units of antitoxin in his office, but it was six years old. He feared it was too old to be useful. The child died the next day.

The following day, a seven-year-old girl was diagnosed with diphtheria. She died later the same day. It was clear to Dr. Welch that the town of Nome was facing an epidemic. Dr. Welch called a town council meeting to discuss the situation. He told city officials he needed at least one million units of serum to hold off the spread of diphtheria. Telegrams were sent to Governor Scott Bone and the U.S. Public Health Service in Washington, D.C. asking for assistance in obtaining the antitoxin. By January 24, there were two more deaths and twenty more confirmed cases. The epidemic promised to wipe out the entire city of Nome if the medicine didn’t arrive. Finally, serum was found in Anchorage. Governor Bone was faced with the difficult decision of how best to safely deliver it to Nome.

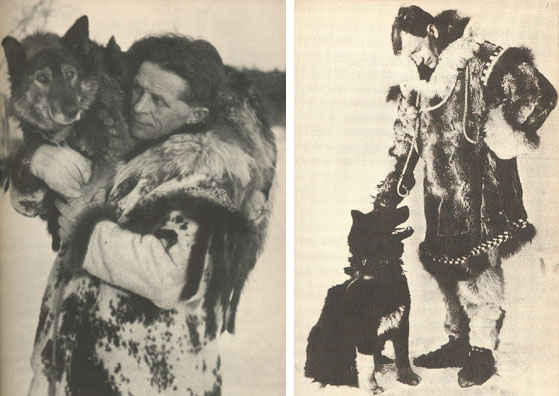

There were only two choices: deliver it by airplane or by dogsled. In their book, The Cruelest Miles, Gay and Laney Salisbury say that many Alaskans believe their state would not have developed were it not for sled dogs. They quote a sled driver as saying, “A man is only as good as his dogs when he is on the trails of Alaska…and a dog is only as good as his feet.”

Governor Bone weighed the risks of both choices. The bush planes available in Alaska had open cockpits and water-cooled engines. Flying an airplane in fifty degree below zero weather was too big a risk. The Board of Health also rejected the use of an airplane. They voted unanimously for the dogsled relay. Governor Bone enlisted the most experienced dogsled racers to help get the serum from outside Anchorage to Nome. Only expert dogsled racers could make this journey of mercy in the middle of the worst winter since 1905. All told, there were twenty men and 150 dogs called upon to make the run. These brave drivers would have to drive a team of dogs day and night over 674 miles to bring the life-saving serum to Nome.

On Tuesday, January 27, 1925, a musher named “Wild Bill” Shannon left Nenana on the first leg of the race. He was a fearless mail driver who was known to take risks, no doubt an explanation for his nickname. He was handed the twenty-pound package at the Nenana train station. He and his nine-dog team would bring the serum from Nenana to Tolovana, where another musher would take over. Because the temperature was approaching fifty below zero, by the time Shannon arrived at the first roadhouse, (a small shack where he and the dogs could rest) he had severe frostbite on his face. After resting four hours, he headed back into the storm to bring the serum to Tolovana. Three of his dogs had to be left at the roadhouse because the below freezing temperature had taken its toll on them. Shannon arrived at the roadhouse in Tolovana at 11 A.M on January 28th. The temperature was 62 degrees below zero.

Mushers and about 150 sled dogs relayed the antitoxin 674 miles (1,085 km) by dog sled across the U.S. territory of Alaska in a record-breaking five and a half days, saving the small city of Nome and the surrounding communities from an incipient epidemic. Both the mushers and their dogs were portrayed as heroes in the newly popular medium of radio, and received headline coverage in newspapers across the United States. Balto, the lead sled dog on the final stretch into Nome, became the most famous canine celebrity of the era after Rin Tin Tin, and his statue is a popular tourist attraction in New York City’s Central Park. The publicity also helped spur an inoculation campaign in the U.S. that dramatically reduced the threat of the disease.

Wow, awesome! Thank you, Stella, I’m honored. My love for dog mushing knows no bounds, and the first two weeks of March, it is all focused on this race. It helps a lot that I personally know (in real life!) a number of the mushers.

The history you quote is quite thorough, but I will take issue with one small point: the native village of Holy Cross, just a few miles away from Nome. Holy Cross is not just a few miles from Nome; it is a few miles from Shageluk, which is 500 miles from Nome. Picky, I know.

An interesting story came out of the race two days ago. Linwood Fiedler is a 65-year-old musher who is running his 25th Iditarod this year. On Tuesday as he was leaving Rohn checkpoint, his sled slammed into a nearly-buried treestump. The carabiner holding the gangline to the sled broke. [Terminology sidebar: the gangline is the line stretched out in front of the sled to which all the dogs are attached. The carabiner is a D-shaped link that attaches the gangline to the sled.] The result was that the sled came slamming to a halt (and Linwood was lucky he didn’t get thrown off and injured from the impact) and the dog team took off, still hooked to the gangline but with no load to pull. They rocketed away in the blink of an eye, and with no load slowing them down, became a tangled mess with some dogs getting dragged, wrapped up in lines, snarling and fighting for their lives. Dogs are often killed by such an accident.

Linwood was left in silence with a fully loaded sled (probably 200+ pounds of gear). He tried to drag the sled himself and took off after the dogs but it was hopeless without help. The race rules allow mushers to help each other in such situations, but no one outside the race can help. If a snowmachine came by and offered him a lift, he’d be disqualified. Fortunately another musher came by and stopped to help. They attached Linwood’s sled behind the musher’s sled and his team pulled both sleds for many miles. It was night, and as they crossed a river Linwood was sweeping the banks with his headlight trying to find his dogs. Suddenly, about a mile away downriver (which was not on the race trail) he saw the red eyes of his dog team reflecting back his headlight. They were in a huge tangle, caught up by a frozen tree limb. If it hadn’t been nighttime, he’d have never seen them. If they’d gotten a little further before getting snagged, he’d have never seen them.

Linwood and the other musher were able to get to them, get them untangled and reattached to his sled. And miracle of miracles, no dogs were dead and there were only minor injuries. Since he received no outside help, Linwood was not disqualified. Miracles happen, and what a blessing.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You sure are correct about the distance from Holy Cross to Nome. I know that came from an outside source (I thought it was at the link I included for the Iditarod history, and it may have been when I originally linked it). Even Wikipedia refers to “the nearby village of Holy Cross.”

That’s quite a story about Linwood Fiedler!

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a story, Tundra! So glad no one–canine or human–was injured. Are such hazards considered part of the race?

Thought Stellars would enjoy some photos of the area around the town of Willow…

LikeLiked by 2 people

SUMMERTIME!! Yowza. Looking out my window at the blizzard that is falling (on top of the 3 feet already there), it’s hard to imagine. Willow is a beautiful town.

Yes, indeed, Lucille, it’s all part of the race. Or rather, it’s just all part of dog mushing. It is WILD out there, and you and your dog team are truly on your own. Back in 1985, the one and only time the great Susan Butcher scratched from Iditarod was when she and her team encountered a moose on the trail who refused to move and who couldn’t be detoured around. Dense woods, deep snow, narrow trail, unyielding moose. After a standoff, with Susan yelling, banging things, trying to scare the moose into leaving, the moose charged her team. Stomped her leader and a team dog to death, and seriously injured 13 more. Susan was devastated. She carried a rifle and a sidearm in the dog sled at all times after that experience. And then won the Iditarod in ’86, ’87, ’88, and ’90. In ’89 she came in second by 1 hour 4 minutes, after 11 days of racing.

I’ll mention again (ICYMI), for those who like to read, get a copy of Winterdance by Gary Paulsen. Lots of great stuff about mushing–and making rookie mistakes–but mainly because it may be the funniest book you ever read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For more about Susan Butcher, I wrote about her passing here:

http://tundramedicinedreams.blogspot.com/2006/08/passing-of-legend.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

How awful for Susan! Something a person would never forget. The moose thought the dogs were wolves, apparently.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nic Petit has retaken the lead. He blew through the checkpoint at Iditarod about 45 minutes ago and sucked all the air out of the place with the energy and power of his team. After finishing his 24 in Ophir, he covered the 80 miles to Iditarod in under 10 hours. Joar arrived in Iditarod a half hour behind Nic; Joar did the same 80 miles in 13 and a half hours after finishing his 24 in Takotna. Aliy, doing her 24 in Iditarod, took 17 and a half hours to get there from Ophir. Part of that difference in speed is in the fact that the guys were rested and she was exhausted. She said she has had a total of 4 hours of sleep since leaving Anchorage.

Nic has moved on down the trail to rest, and Joar is resting in Iditarod, probably for 2-4 hours. Aliy can’t leave until about 3 am tomorrow morning. The pundits on the trail are referring to Nic’s team as “a pack of raging buffalo”. They are strong, they are loud, and they are fast. Joar’s team is also looking strong and fast. As fast as Nic’s? That remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, Pete Kaiser is doing well, in 3rd position, now about 30 miles from Iditarod and finished his 24. And Jessica Klejka is hanging in there in 41st position. She is the 5th place rookie right now, and has finished her 24 in McGrath. So far, only one team has scratched (dropped out of the race), Shaynee Traska, a 30-year-old woman from Michigan. This was her second Iditarod start; she finished the race last year. Most years see at least a half dozen teams scratch, sometimes as early as the first checkpoint at Yentna.

Go dogs! Go Aliy!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sigh…and the best I can say about our dogs is they’d turn the AC up, sit back in a recliner, pop a beer and watch the race. “What!? Pull a what!? How $%#@& far!? Are you outta your rabbit%$$#@ mind!?”

LikeLiked by 2 people

One of my sled dogs must have been their cousin. When I hooked him up with the team, he didn’t just run along without pulling; no, he lay down and made the team drag him. He refused to get up. His name was Bear, and he spent the rest of his life as a house dog couch potato. I just lost him last year, at age 16, and I still miss him.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Ours do some work as far as killing snakes, chasing wild hogs, warding off strangers and telling us, as we step out of the shower: “WOOF! Have you lost weight!?”

I guess that works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sound like good dogs to me!

LikeLike

We haven’t kicked them off the couch lately.

LikeLike

Mine firmly believes that a dog’s place is on the couch. Or the bed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Or in the fridge…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonder if this will work…

https://iditarod.com/jessica-klejka-through-takotna/

LikeLike

Oh good. I pay the $35/yr fee to be an Iditarod Insider, and I never know exactly what is in the public domain. I wish I could share the Insider videos with you. They cover Aliy a lot.

LikeLike

I like seeing the maps a lot, too, Stella, and always appreciate hearing about the current efforts on the Iditarod. What a classic event – – – Love all your input, Tundra PA. Good times….

It’s been snowing off and on for a couple of weeks here in central Oregon – some areas both south and north have had heavy and damaging snow where it’s not an “off and on” thing at all. But today – I did have to say something to a local who was whining a bit about “It’s snowing …. AGAIN” – – – pointed out to her that at least it wasn’t below zero. It was in the mid-30s at that point. However it has been a much colder than usual (for Oregon) winter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just found this…

“Endurance battle: Wolf attempts a solo moose hunt in north Ontario”

(btw, in case you’re squeamish, this vid is safe for all to watch)….

By SARAH KEARTES OCTOBER 11, 2017

https://www.earthtouchnews.com/natural-world/predator-vs-prey/endurance-battle-wolf-attempts-a-solo-moose-hunt-in-north-ontario/

LikeLike